"The Rhetoric of History" from Doing History, by J. H. Hexter

"The Rhetoric of History" from Doing History, by J. H. Hexter

Mays employs the rhetoric of action, the most common and universal method of demonstrating that one knows... but by the unique and unreplicable perfection of his response. [could be added to ERASABILITY]

not a ture narrative explanation determined by the logic of casual ascription but the historical story truest to the past... providing increments of knowledge and truth about the past.

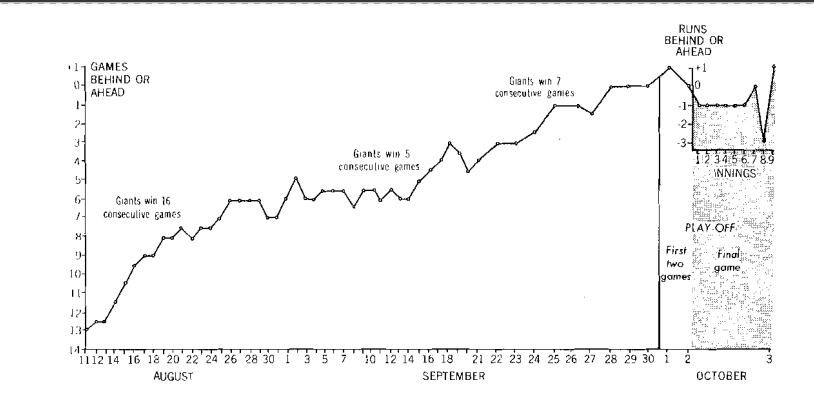

Figure: The positions of the New York Giants in relation to the Brooklyn Dodgers in the 1951 pennant race. (Above)

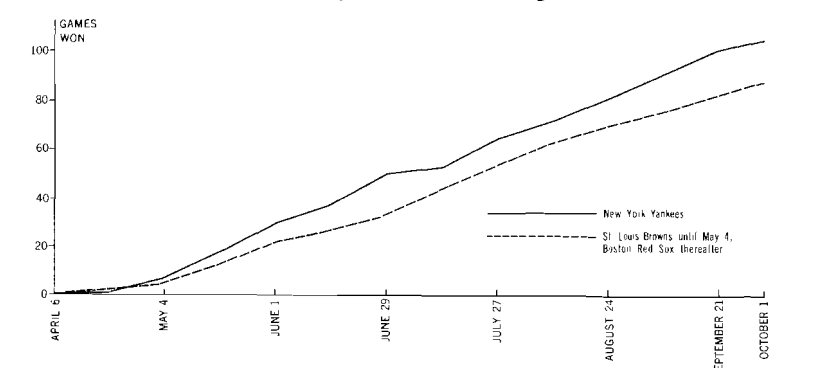

Figure 2: The positions of the New York Yankees and the second-place American League team in the 1939 baseball season.

On the basis of true narrative explanation determined by the logic of causal connections, it proved impossible to determine where to begin the historical story of the 1951 pennant race or what dimensions to give to any of its parts. Indeed, since causal connection is subject both to infinite regress and to infinite ramification, and since that historical story and ay other must have a beginning and finite dimensions of its parts, it is in principle impossible on the basis of the logic of narrative explanation alone to tell a historical story at all. On the other hand, the rhetoric of historical storytelling provided us with the means of recognizing whether there was a historical story to tell where the story should start, and roughly what the relative dimensions of its parts should be.

The historical storyteller's time is not clock-and-calendar time; it is historical tempo.

Correct determination of historical tempo and the appropriate correlative expansions and contractions of scale in a historical story depend on the examination IN RETROSPECT of the historical record. That is to say, when the historian tells a historical story, he must not only know something of the outcomes of the events that concern him; he must use what he knows in telling the story.

they do not know the writer's construal of the outcome, since not knowing it whets their curiosity and intensifies their engagement and vicarious participation in the story, thus augmenting their knowledge of the past.

On August 11, at the point of maximum distance between Brooklyn and New York, no one forsaw or could have forseen that New York was on the point of beginning a sixteen-game winning streak that transformed the baseball season into a pennant race...

historical analysis

the sciences have no rhetoric

Bobby Thomson's home run, the defeat of the Armada, the battle of Stalingrad, the Normandy landings.

what they want is confrontation with the riches of the event itself, a sense of vicarious participation in a great happening, the satisfaction of understanding what those great moments were like... [The Western Tradition, both what everyone partakes in and to do with those who write it and impart it to others]

The normally cool Russ Hodges, who went berserk and screamed, "THE GIANTS WIN THE PENNANT!"

To tell the truth about the past, the historian must marshal resources of rhetoric utterly alien to the rhetoric of the sciences in order to render his account forceful, vivid, and lively; to impart to it the emotional and intellectual impact that will render it maximally accessible and maximally intelligible to those who read it.